Saving and Investment Equality

Say’s Law of Markets

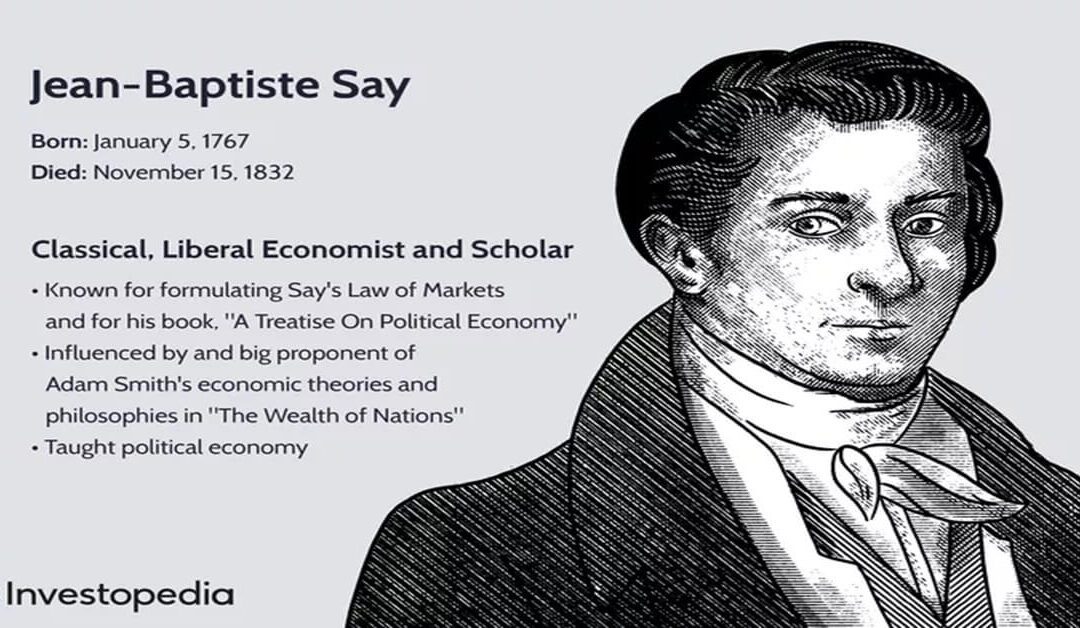

Say’s Law of Markets is a key concept in classical economic theory, introduced by 19th-century French economist J.B. Say. It is based on the idea that “supply creates its own demand.” This means that as goods are produced, they generate income, which in turn creates demand for those goods.

1. Production Creates Demand for Goods

When producers make goods, they pay wages to workers and spend on other inputs. Workers use these wages to buy goods, creating demand in the market. Essentially, production and demand go hand in hand.

2. Based on the Barter System

Originally, Say’s Law applied to a barter economy, where goods were exchanged directly for other goods. In such a system, whatever is produced is ultimately consumed. Even in a money-based economy, the idea remains that production generates income, which fuels demand.

3. No General Overproduction

Say argued that general overproduction (where the economy produces more than it can consume) is unlikely. People only produce goods they intend to exchange for something they need. While a specific product might be overproduced due to incorrect demand estimates, this is a temporary issue that can be corrected.

4. Support from J.S. Mill

Economist J.S. Mill agreed with Say’s Law, emphasizing that general overproduction and unemployment are improbable. Increasing production leads to more jobs, higher incomes, and greater profits.

5. Saving and Investment Balance

Not all income is spent on consumption—some of it is saved. Say believed that these savings are automatically invested, fueling further production. This balance between saving and investment prevents overproduction.

6. Role of Interest Rates

Interest rates help maintain the balance between saving and investment. If investment exceeds saving, interest rates rise, encouraging more saving and less investment. Conversely, if saving exceeds investment, interest rates fall, encouraging more investment and less saving.

7. Labour Market and Employment

Say’s Law also applies to the labour market. Economist Pigou argued that if wages are flexible, more workers can be employed. Free competition ensures that wages adjust to match demand, reducing unemployment. However, laws like minimum wage or demands from trade unions can disrupt this balance.

Say’s Law: Key Propositions and Implications

Say’s Law provides valuable insights into how markets function. Here are the main propositions and their implications:

1. Full Employment in the Economy

The law assumes that the economy operates at full employment. This means all resources are utilized, and increasing production leads to more jobs for workers and other inputs. Production continues to grow until the economy reaches its maximum capacity.

2. Efficient Use of Resources

At full employment, no resources are left idle. This ensures proper utilization, resulting in higher production and more income for everyone involved.

3. Perfect Competition in Markets

The law assumes a perfectly competitive environment in both labour and product markets, supported by the following conditions:

a) Market Size:

The market is large enough to create demand for all goods, with supply and demand driving the market forces.

b) Automatic Adjustments:

Markets naturally self-correct. For instance, in the capital market, interest rates balance savings and investments. Similarly, wage rates ensure equilibrium between labour demand and supply.

c) Neutral Role of Money:

The law operates as if it’s a barter economy, where goods are exchanged for goods. Money simply facilitates transactions without affecting production.

4. Laissez-Faire Policy

Say’s Law assumes a capitalist economy that follows the laissez-faire principle, meaning minimal government interference. This allows markets to self-regulate and achieve full employment equilibrium.

5. Saving as a Social Virtue

The income earned by individuals is spent on goods they help produce. Any portion saved is automatically invested back into the economy, driving further production. Thus, saving is considered a social good that supports economic growth.

Criticisms of Say's Law

Economist J.M. Keynes, in his General Theory, strongly criticized Say’s Law of Markets.

1. Supply Does Not Automatically Create Demand

Say’s Law assumes that producing goods automatically creates demand for them. However, Keynes argued that in modern economies, production often outpaces demand. People do not necessarily consume all the goods produced within the economy, especially when demand lags behind supply.

2. No Automatic Self-Adjustment

Say’s Law claims that markets naturally adjust to maintain full employment in the long run. Keynes disagreed, famously stating, “In the long run, we are all dead.” He argued that unemployment persists unless addressed directly, and increasing investment—not waiting for markets to adjust—is the solution.

3. Money is Not Neutral

Say’s Law downplays the role of money, treating it as a neutral medium of exchange. Keynes, however, emphasized that money influences economic activity. People hold money for various reasons—such as emergencies or future business needs—making money a significant factor in economic decisions.

4. Overproduction is Possible

Say’s Law claims there cannot be general overproduction because supply creates demand. Keynes countered that not all income is spent on goods—some is saved, and savings are not always invested. This mismatch can lead to overproduction and unemployment.

5. Underemployment is Common

Keynes argued that full employment is rare in capitalist economies. Supply often exceeds demand, leaving many workers unemployed even if they are willing to work at lower wages. This underemployment undermines the assumptions of Say’s Law.

6. Need for State Intervention

Say’s Law relies on a laissez-faire approach, assuming markets can self-correct. Keynes highlighted how this approach failed during the Great Depression, causing widespread unemployment and overproduction. He advocated for active government intervention through fiscal and monetary policies to balance supply and demand.

7. Income, Not Interest Rates, Balances Saving and Investment

Classical economists claimed that interest rates balance savings and investment. Keynes disagreed, arguing that changes in income, not interest rates, ensure this balance.

8. Wage Cuts Don’t Solve Unemployment

Say’s Law proponents like Pigou believed cutting wages could reduce unemployment. Keynes opposed this idea, stating that wage cuts actually worsen unemployment by reducing workers’ purchasing power. Instead, he supported flexible monetary policies to boost employment.

9. Demand Creates Supply, Not the Other Way Around

Keynes rejected Say’s assertion that “supply creates its own demand.” He proposed the opposite: “Demand creates its own supply.” According to Keynes, unemployment stems from insufficient effective demand—when people do not spend enough of their income on goods, demand weakens, leading to job losses.

Summary

Say’s Law suggests that a free-market economy naturally balances production, demand, and employment over time. While short-term imbalances can occur, the system tends to correct itself, ensuring full employment and efficient use of resources.

Say’s Law emphasizes full employment, efficient resource use, market competition, and the importance of savings in fostering economic progress. By trusting in the market’s ability to self-adjust, it highlights the natural balance between supply and demand.

Keynes’s critique of Say’s Law reshaped economic thought, emphasizing the importance of demand, government intervention, and active policies to address unemployment and economic imbalances. His ideas remain foundational in modern macroeconomics.